An Interview with Michael N. McGregor

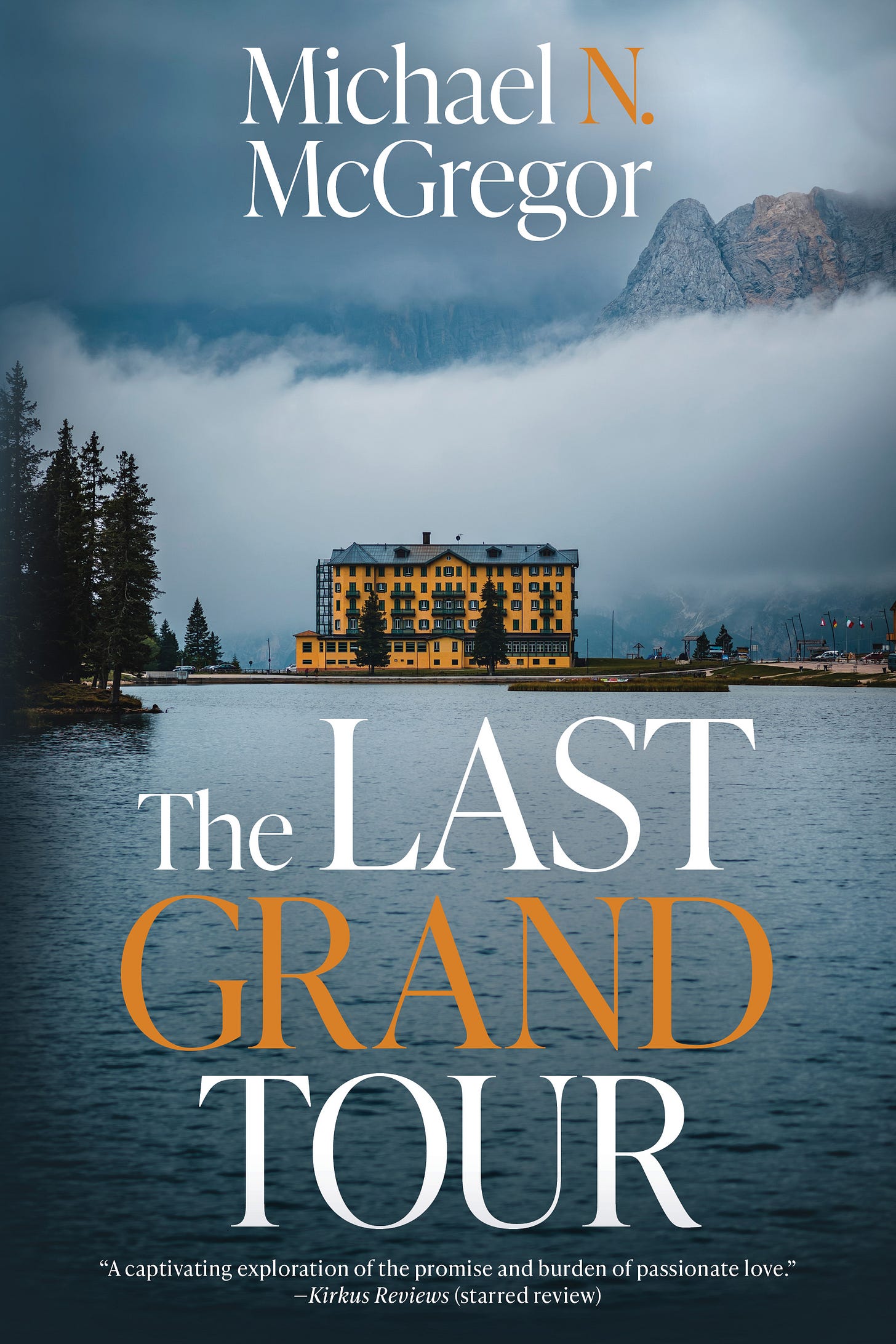

The Last Grand Tour

Good morning fellow book nerds and eager readers. Today I have the immense pleasure of introducing you to Michael N. McGregor and his latest book (launching today), The Last Grand Tour.

I was lucky enough to read an advanced copy, and I have to say, this novel has all the goodies: history, romance, mystery, and exquisite descriptions of Southern Germany and the Northern Italian mountains.

Bonus: Michael was generous enough to indulge my writerly questions. His answers are a master class in craft decision-making.

The interview:

1. Tell us how long you spent writing The Last Grand Tour.

Longer than I’d like to admit. I finished the first version twenty-some years ago. I had an agent then who couldn’t sell the book. She suggested I put it in a drawer and work on the next one, which I did, reluctantly and maybe foolishly. Over the years, I’d take it out now and then and rework parts of it. I always loved the story, the characters, and the setting but I never tried to publish it again. Then, about two years ago, I read through it one more time and thought, This is a good book. I made a few more changes and sent a synopsis to Michael Schepps at Korza Books, asking if he might be interested. He asked to see the full manuscript … and here we are!

2. The theme of “madness” permeates the novel, drawing on historical tidbits from the “Mad King Ludwig” lore. In what other ways did history inform the current-day architecture of your novel?

In important ways, The Last Grand Tour is a book about history, or rather histories, both general and personal. The title itself is a reference to an earlier age of European travel. And throughout the story, the past is always intruding on the present. In the first scene, when Joe meets Tonia, he’s thinking about his history with his wife. And on the first drive, it’s Rudy’s objection to what Joe leaves out of his history of Munich that leads to the first clash, the first revelation, the first suggestion that things aren’t what they seem.

The story is set a few years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, a period when Europe was opening up but also dealing with a darker history, much as the book’s characters are. Revelations of personal histories propel the story forward, igniting conflict but also increasing our understanding of—and our sympathy for—the characters. (At least I hope they do!)

Ultimately, “history” isn’t what happened but rather the story told about what happened. And The Last Grand Tour is a book about stories, including those we tell ourselves about our own past. One of main themes I wanted to explore in the book was the interplay between fantasy and reality, what we believe and what is true. It’s a theme that seems more resonate today than ever.

3. You evoke the richness of the mountain lands of Germany, Italy and Austria so vividly. Did you spend much time in that area yourself? And in what capacity?

My introduction to Europe was a snowy weekend in Berchtesgaden tacked to the end of a round-the-world trip because a friend had taken a job there. I fell in love with the region immediately—the mountains, the customs, the people, the history. Two years later, I returned to explore it more thoroughly as part of an eight-month trip through Europe and the Middle East. Then, for over a decade in the ‘80s and ‘90s, I earned my living leading Americans on tours through different parts of Europe, including those lands. I continued to explore them on my own too.

4. Venice—somewhat like the video gaming backdrop in the narrative—seems to be a sort of elusive Grail object in your book. The last sentence of one of the latter chapters reads: “How much more like the city I wished it to be would Venice have looked to me then.” Without giving away spoilers, can you speak about the metaphor of romantic illusion that runs through the story?

One of the book’s main questions is: What is illusion and what is real? The narrator, Joe, considers himself a Romantic (both big and little R). But he’s been dis-illusioned, so to speak. He’s lost the passion he thinks is central to seeing clearly and feeling fully alive. Then he meets a smart and charming artist who seems to share his beliefs and hopes. As his passion returns, he has to decide whether what is happening is real. As a tour guide who’s used to embellishing facts he knows how easily reality can be distorted.

5. You chose to filter this story through one character: Joe. How did you navigate and pace the sprinkling of secrets that Joe (and the reader) would uncover by novel’s end?

I started by mimicking a tour guide’s experiences. When a group shows up, you know nothing about them. Over two or three weeks, however, as you spend days and nights with them, you learn more and more. You hear their stories, observe their actions, listen to their words. Along the way, you try to assemble a picture of them from pieces that emerge in somewhat random order.

A novel can’t be entirely random, though. So I took advantage of the fact that people tend to reveal themselves most at tense moments, especially when traveling. While some of those moments are shared, most are highly personal. Rudy, for example, reacts to being in the city where Hitler gained power. Felicity opens up when she visits a city she always wanted to sing in. And Tonia talks about her past when she returns to a place she went with her husband.

Because Joe is present for each of these revelations but doesn’t have the context necessary to understand them fully, he tries to make sense of them by putting them together with what he already knows. His limited knowledge forces the reader to assemble the bigger story too, deciding along the way whether Joe’s version of things is correct or not. This allows for dramatic reversals. Again and again in the book Joe begins to believe something is true, only to learn or observe something else that makes him see things differently.

The revelations and reversals cause us, as readers, to pay closer attention, challenging our own suppositions of what is true. As our views shift of the various characters, including Joe himself, we find ourselves working down through the onion layers, hoping to reach the core before the tour reaches Venice.

6. The “off-page” character, Gerhard, is a bit of an enigma. He comes across as a quasi-villain but we can’t be certain. Because we don’t know if he’ll ever appear, we’re forced to assess him through the words of others. Can you speak to the role Gerhard plays in the book?

I’ve always been fascinated by characters characterized mostly by absence, known primarily through what others say about them or want from them or fear they might do. Gerhard represents a kind of power or control the characters on the last Grand tour have been temporarily freed from—a power that continues to exist nonetheless.

One of the book’s questions is what they’ll do with this freedom. The first impulse for some is to try to find Gerhard rather than go on without him. But they do go on, and as they do, they’re subject to influences from the past and the present that don’t always fit with those of a successful American businessman.

The mystery of where Gerhard is and why he hasn’t shown up adds a layer of tension to the story, especially as Joe and Tonia grow closer.

There is a palpable undercurrent of romance throughout The Last Grand Tour, and it’s mixed with strong, base drives: hunger, sexuality, creation, the longing for human connection. Yet the characters’ longings are thwarted time and time again. Masterfully, I might add. But often fledgling writers reject throwing their characters into peril, thus subverting that all-important page-turning tension and emotional throughline. What advice do you have for aspiring novelists who seek to add tension to their manuscripts?

Every worthwhile writing teacher or writing book will tell you to give your characters strong desires and put obstacles in the way of fulfilling them. But it’s much more than that. A lot of stories fail because a character’s desire isn’t big enough or important enough—to the reader or even to the character. I interviewed a playwright once who told me his teacher in graduate school said that the stakes in any story you write have to be life and death. As soon as I heard that, I knew it was right. It doesn’t mean you have to include the danger of actual death. In many of the best novels or stories, the stakes are life and death only because a character thinks or feels they are. If a character risks everything in pursuit of something he or she feels is of ultimate value or meaning, the cost of failure is a kind of death—of one’s career or relationship or faith or sense of self or ability to go on.

The more desperate a character is and the more chances she takes in pursuit of her desire—or, better still, obsession—the more perilous every obstacle or reversal becomes. Once you have a character in a situation like this, you can increase the pressure—the tension—in all kinds of ways. Having an off-stage character who might show up and disapprove of what your character is doing is one way. Putting your character in possible physical danger is another. You can start a clock ticking, or have your character discover something that increases her desire, or put her at odds with someone or something able to thwart her pursuit. Conflict, whether overt or—better still—latent, causes tension.

Think about a story such as the movie version of “The Wizard of Oz.” What causes the tension there? A vulnerable girl far from home in a strange land, a deep desire to return to where she came from and those she loves, an unknown destination, a path of indeterminate length that leads through dark and frightening woods, a witch who is willing to kill her for something (the ruby slippers) the girl needs to fulfill her desire, those hideous flying monkeys and grasping trees, the incompetence of her traveling companions, the need to protect her beloved dog, the sense that the longer the journey lasts the worse it will be for her, the series of grim surprises that makes us apprehensive about what might happen next, even the angry projection the “wizard” uses to try to scare her away.

The key is to think about your character’s desire and journey deeply enough to see what might be used to cause a sense of peril in your reader, and then use everything you can to put the character’s success at risk. It helps if you can seduce your readers into cheering for your character too, engaging them at the deepest emotional level. Tension comes in large part from making your reader care and then putting the person they care about at risk in whatever way you can. The more human the situation and stakes, the deeper that care—and the resulting concern—will be.

Intrigued? Meet Michael in person!

Upcoming events for The Last Grand Tour (all events are free and open to the public):

Tuesday, January 28–3 p.m.–"From Manuscript to Marketplace: The Last Grand Tour’s Collaborative Journey," panel discussion with the Korza Books publisher Michael Schepps, editor Molly Simas, and book designer Olivia Croom Hammerman, Portland State University, FMH 302, Portland, OR.

Tuesday, January 28–7 p.m.–Book launch (with Brian Lindstrom), Powell’s Books, 1005 W Burnside St, Portland, OR

Thursday, January 30–6 p.m.–(with Gene Openshaw) at the Edmonds Bookshop, 111 5th Ave S, Edmonds, WA

Thursday, February 6–6 p.m.–(with Gene Openshaw) at Village Books, 1200 11th Street, Bellingham, WA

Tuesday, February 11–7 p.m.–Seattle launch, Third Place Books Ravenna, 6504 20th Ave NE, Seattle, WA

Tuesday, February 18–6 p.m.–Tattered Cover Book Store, Aspen Grove, 7301 South Santa Fe Drive, Littleton, CO

Monday, March 17–6 p.m.–Auntie’s Bookstore, 402 W. Main Avenue, Spokane, WA

For a regularly updated list of book-related events, go to michaelnmcgregor.com/appearances

Buy your very own copy of The Last Grand Tour: https://bookshop.org/a/84534/9781957024103

About Michael:

Michael N. McGregor is a fiction writer, essayist, and biographer whose first book, Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax, was a finalist for a Washington State Book Award and chosen by the Association of University Presses as a top-ten book in American Studies for libraries. His short stories, essays, and articles have appeared in a wide variety of journals and magazines, including Tin House, StoryQuarterly, Poetry, Orion, the South Dakota Review, and Poets & Writers.

Before earning his MFA at Columbia University, McGregor worked as a writer for a relief and development magazine, specializing in Asia. Later, he spent a decade guiding Americans through Europe. After a long career as a professor of creative writing—including 17 years at Portland State University—he returned to his hometown, Seattle, where he runs the website WritingtheNorthwest.com and hosts the Cascadia Writers-in-Conversation series.

McGregor’s next book, An Island to Myself: The Place of Solitude in an Active Life, will be published by Monkfish Publishing in May 2025. The Last Grand Tour is his first novel. To learn more about him and his writing, go to michaelnmcgregor.com

I can't wait to buy a copy of this book!

You know, when I was an undergrad at PSU in the early 2000s, Professor Michael McGregor taught writing and every term, for YEARS I would try to register for one of his classes and they were always snatched up. I believe I spoke to him one time on the phone, and he was so gracious and kind. I will be buying a copy of his book, come payday. Thank you Suzy for a great post here.